The Fitwell Story

Fitwell Buckles' journey began in a swimming pool in 2022 while on vacation. As most watch wearers know, wrist size can change based on time of day and temperature, and when walking from an air conditioned hotel room to a warm outside environment and then to a cool swimming pool, the problem became even more noticeable. Making matters worse, our wrist size usually didn't match any of the standard holes in the watch strap. There were few simple solutions to the problem, and we thought there must be a better way than cutting out one of the holes with a razor blade.

The Challenge

A great watch that doesn't fit well cannot be truly appreciated. Most metal bracelets can be adjusted with full links, half links, and a micro-adjustment. But the rubber strap we had installed on our Seiko SPB313 was stuck with standard hole spacing about 8mm apart. Why couldn't rubber, leather, or textile straps offer micro-adjustment like steel bracelets?

Phase I

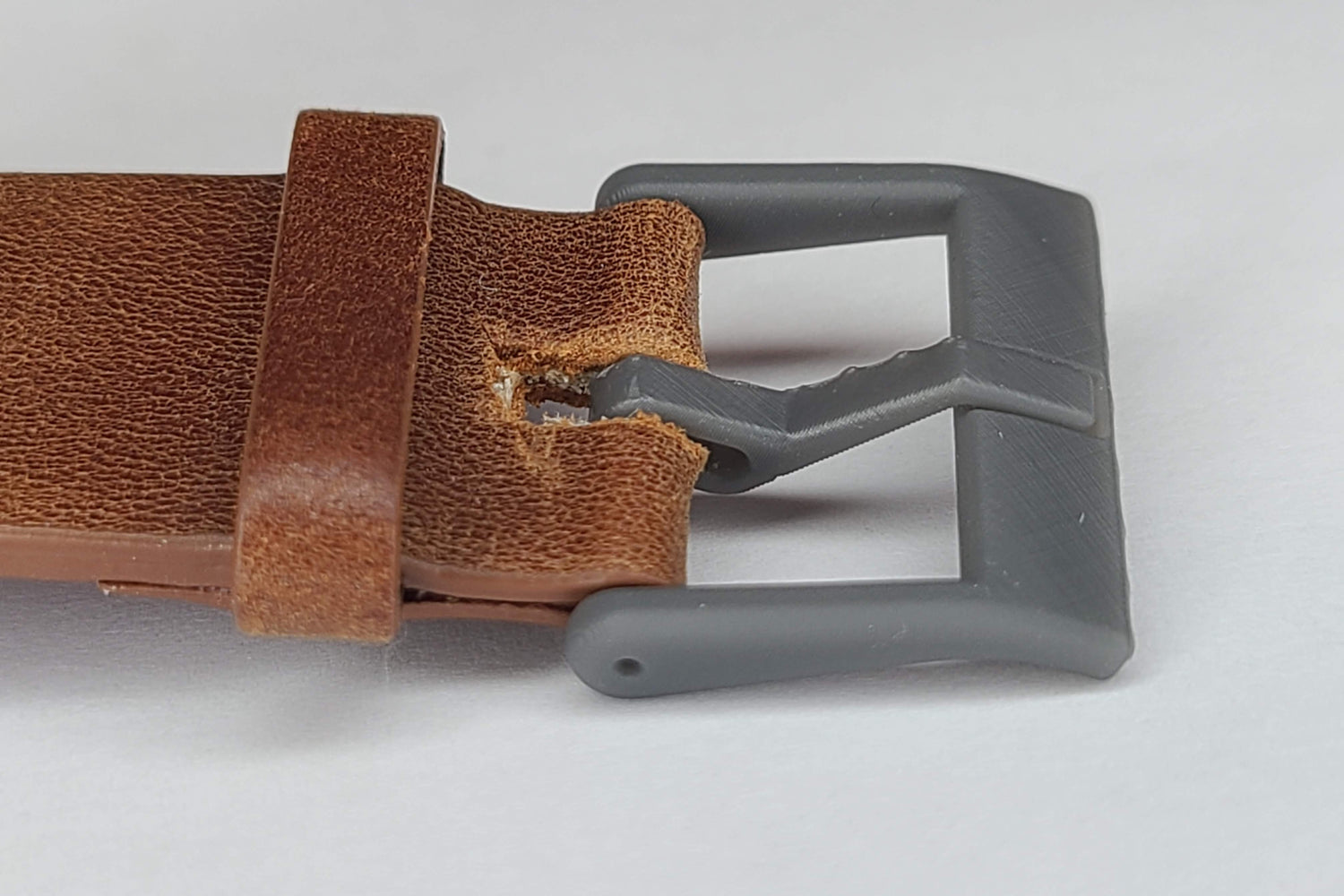

We decided that a conventional looking buckle with a tang that could snap between two positions, spaced "half of a hole" apart, would be a good place to start. One provisional patent later (USPTO 63/438,718) and the Model One was born. While our first prototype fundamentally worked, it had many shortcomings, the most significant of which was that the strap needed to be modified in order to accommodate the base of the tang.

Phase II

Several iterations later, we decided that moving the tang to its own pin would allow it to move back and forth as needed without interfering with strap. The downsides were that the buckle was less attractive, very long, and more expensive. But it did work better and we commissioned our first samples out of 316L stainless steel.

One of the challenges we faced with this design was that the strap was prone to "hiking" up over the tang when the buckle was set to its tighter position. In addition to bad, it made the tighter position less tight, lessening the effective adjustment range. Several ideas and different tang iterations came and went, each bringing improvements but also compromises.

The next iterations focused on the shape of the buckle and included a curved bridge to help keep the strap from climbing up the tang. That worked...but made it more difficult to thread the strap through the buckle when putting on the watch. A more compact design was tested, but again, the user experience suffered. We were also concerned about causing too much wear and tear on the edges of the watch strap, so this version never made it past the rapid prototype phase.

In what would prove to be the final chapter of our Phase II design, the curved bridge was replaced in favor of a conventional straight bridge with wings added to help keep the strap in check. The final hurdle of this design - ease of use - was never resolved, and we decided that this design concept had run its course after nearly 60 different tang designs and several hundred buckle iterations.

Phase III

For Phase III, we went back to the figurative drawing board. We'd learned a lot about the snapping action of our 316L stainless steel tangs, and were able incorporate that knowledge into a design that we'd previously been unable to manufacture: moving the snapping action from the tang to the buckle itself.

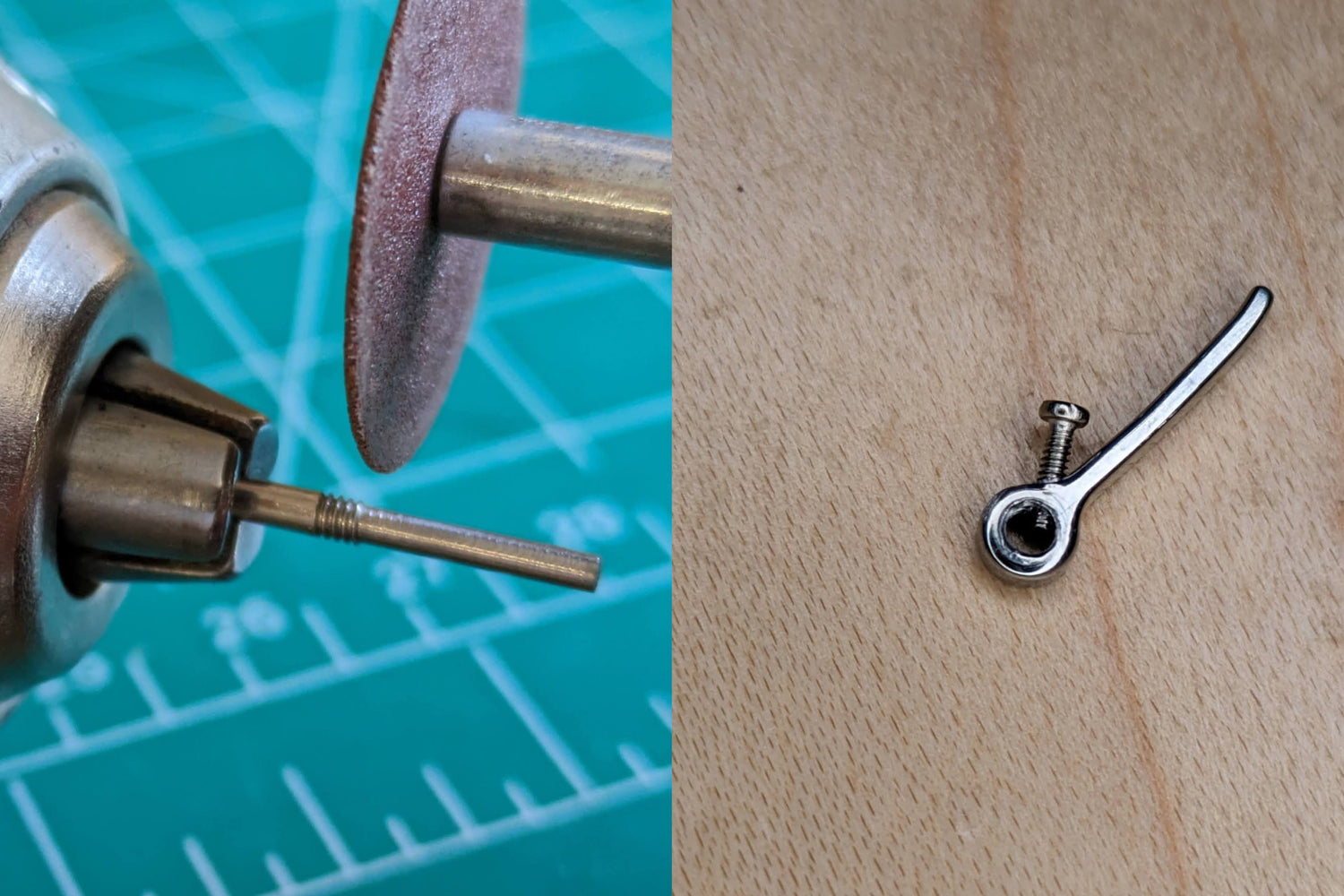

Version 7.0 of the Model One was all about testing different spring bar and buckle arm designs to try to achieve the tight tolerances needed for the buckle to work properly. Since conventional spring bars were not designed for the type of loads involved in snapping the buckle from one position to the next, we set about designing our own.

Early samples showed promising overall performance - it would just come down to making the snapping tension strong enough to hold position, but easy enough to move without damaging the strap when snapping between positions. Another provisional patent was filed (USPTO 63/619,310) and we set about solving the remaining challenges.

One of the biggest difficulties we encountered was getting the tang to lock on to our new spring bar design. Our first concept used a threaded bar and tang but the tang would loosen with use. Adding a set screw helped, but the hardware was very small and delicate. We decided that it would make installing the buckles too complicated and would require a special tool.

After a lot of testing, we were able to refine the geometry of the buckle so that it would hold position with a very light snapping tension, freeing us up to use a more conventional spring bar. During our product durability testing, we actually tore through the nylon strap on our testing rig, reaching nearly 20lbs / 9kg of force without failure.

Even though it was now basically impossible for the watch buckle to accidentally adjust by itself, we were able to retain a very light snapping action that could be adjusted with two fingers while the watch was still on the wrist.

Production Fitwell Model One

After nearly two years in development and 334 design iterations, the first Fitwell Model One buckles rolled off the production line and hit the market.